On October 10, 2021, during anticipated legislative elections, Iraqis gathered to elect the 329 new deputies of the Majlis al Nuwab, the national parliament. These elections were organized by the Iraqi government in order to calm the anger of the Iraqi street that emerged during massive demonstrations in October 2019, which lasted for several months, and forced Prime Minister Adil Abdul Mahdi to resign from his position.

Among the parliamentary seats that were to be filled, nine are usually allocated to minorities according to the electoral law. 2021’s elections were unprecedented as they implemented a new electoral law, which among other things, redefines the electoral districts, switching from the voting circonscriptions previously related to the 19 governorates, to a 83 electoral districts system. This is a significant change in the Iraqi electoral process. Minorities in particular saw it as an opportunity to strengthen their representation within Iraqi institutions.

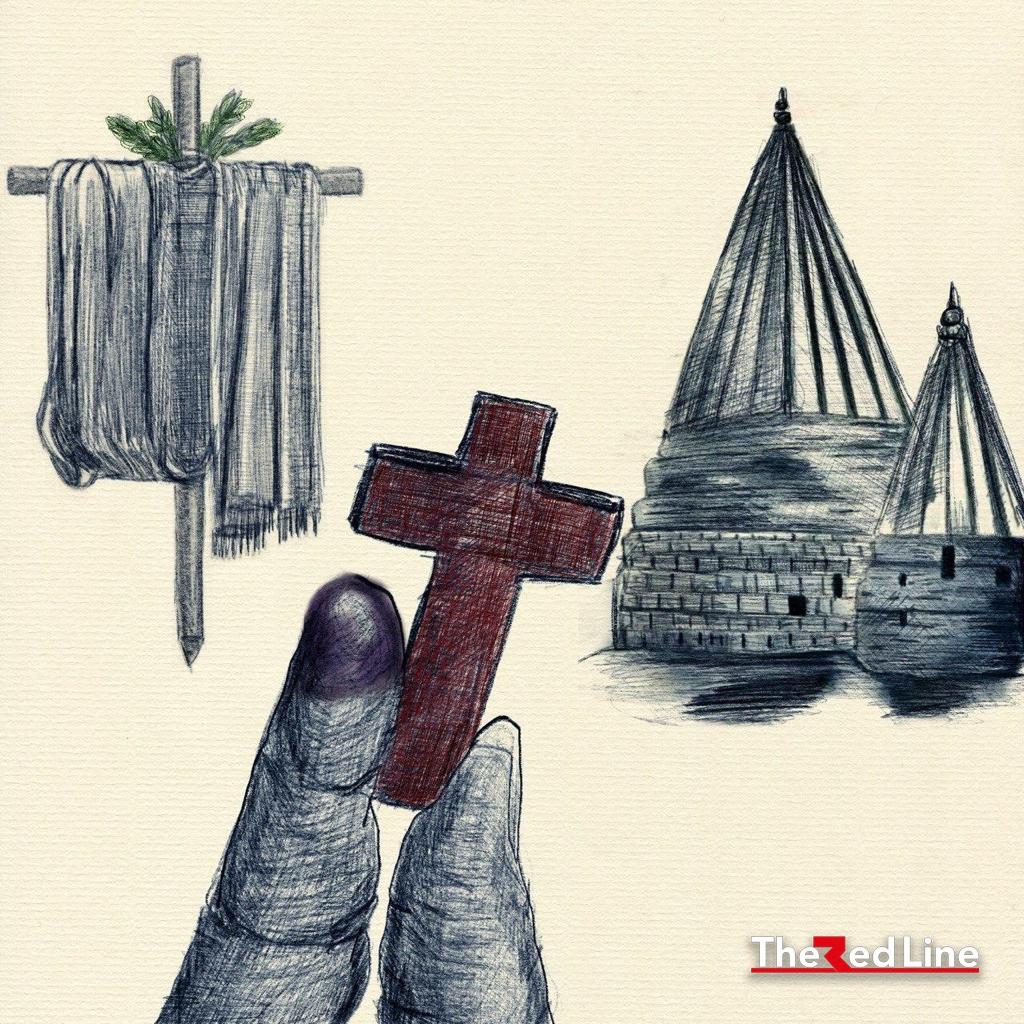

Of these nine seats for minorities, the Christian component obtained five places in a single constituency for all of Iraq. These seats were coveted by 35 candidates. Eight candidates contested the only seat allocated to the Shabaks. The Yazidi minority, meanwhile, was also granted a single parliamentary seat in the governorate of Nineveh, where 6 candidates were vying for it.

Similarly, only one seat was constitutionally reserved for one of the eight candidates from the Sabaean minority running in Baghdad, while this minority exists in other districts of the country. Finally, nine candidates from the governorate of Wasit, in the southern center of Iraq, competed for the only parliamentary seat allocated to the Kurdish Faylis.

According to the final results of the elections, the participation rate reached 44%. The electoral commission confirmed on November 30 the final results which saw the triumph of the current of the Shiite leader El Sadr (now controlling 79 seats in parliament, the largest parliamentary group), representing barely 22% of the seats of the majlis Al Nuwab. Meanwhile, with only 9 seats, minorities do not represent more than 2.75% of the hemicycle. This figure not only fails to represent the demographic weight of the minority groups in Iraq, it also distorts the sense of democratic representation.

The intervention of the big parties

Faced with these constitutional constraints and despite the official guarantees of democratic representation, the Iraqi minorities are also apprehensive about the stranglehold of the major parties over the nine parliamentary seats allocated to them. According to close observers of the Iraqi political scene, the main Kurdish and Shiite parties support candidates from these components and encourage their supporters to vote for them in order to win an additional seat in parliament.

Thus, parties representing minorities accuse the Kurdish Democratic Party and the Shiite Fatah coalition (which brings together parties close to Iran) of sponsoring by votes in order to control the minority quota for the benefit of candidates which they are close to. In this light,the Christian party Abnaa Al-Nahrain made a press statement to discuss its withdrawal from the legislative elections, denouncing the militarization of the Iraqi scene and the interference of the major political parties in its affairs.

On his side, member of the executive committee of the Ibnaa al Nahrain party, Mr. Issam Nissan, explained that his party’s withdrawal from elections is the consequence of the government’s failure to address the issue of minority seats hijacking, in particular the minority groups’ request to restrict the vote for their allocated seats to an electoral college composed solely of members of their respective community. The party expressed this demand in several ways, notably by demonstrating in front of the regional parliament before the elections.

Mr. Nissan argues that the major parties co-opt minority seats in order to increase their weight in parliament, a strategy highly detrimental to the principles of the representation these minority and other vulnerable groups aspire for. “In the end, the electoral quota no longer has any meaning,” he claims.

Also, according to the executive committee member of this party, this flaw in the system is still being instrumentalized on the pretext that the United Nations Organization is opposed to any voting restricted to electoral colleges (which would ensure the autonomy of minorities in the election of their representatives).

Contradicting the theory of minority seat cooptation, the leader of the Babylonian movement, Mr. Rayan Elkildani, points out that the loss of the monopoly of the minority community parties is due to the voters’ disengagement with these traditionalist political actors who failed to preserve and protect Christians’ interests in the past. Their marginalization would therefore only be due to a popular vote sanctioning them and not be the result of any outsiders’ interference.

Cancellation of elections abroad

As several political analysts pointed out, the electoral code of the last elections does not ensure the participation of Iraqis living in diaspora. This decision deprived minorities, very active outside Iraq following their forced exiles, of an opportunity to vote during elections. This had a strong impact on the results.

According to statistics from the Chaldean Church in Iraq, two-thirds of Christians from Iraq had to go into exile. MLore than one and a half million individuals lived in Mesopotamia before 2003, the year of the American intervention in Iraq and the fall of the Baathist regime. Also, roughly one hundred thousand Yedzidis left Iraq since 2014, after the genocide perpetrated by ISIS, according to statistics from the Yazidi Affairs Directorate in Iraqi Kurdistan.

For its part, the Sabean community is the one that experienced the greatest number of departures abroad. Of the seventy-five thousand Sabaean-Mandeans throughout the world, between thirty and fifty thousand Iraq lived around the Tigris and Euphrates rivers. Today, that number has dropped to less than fifteen thousand individuals.

“The law facilitates interventions”

Beyond the issue of diaspora vote, the question of interference remains the main obstacle to the democratic representation of minorities in parliament. An expert in questions of Iraqi cultural and political diversity, Mr. Saad Selloum supports Issam Nissan’s comments. According to him, the new electoral code did not settle the question of interventions from outside the communities by granting the right to vote to all Iraqis in minority electoral districts.

The Christian minority has not escaped this instrumentalization of their electoral seats. This phenomenon is greatly facilitated by the intervention of powerful parties that manipulate election results. For Mmr. Nissan and Selloum, this interference by big parties is illegal and minorities should be able to manage their own political future.

Since the atrocities committed in recent years by the Islamic State organization in Iraq having particularly targeted religious minorities, the question of religious communities in Iraq now has an international dimension. This renewed attention and sympathy towards these vulnerable groups could, however, work to their advantage by making it more difficult for outside interference in their affairs in the future.

For journalist Mohamed Bachir, a member of the Chabak minority, political and sectarian struggles have contributed to the dismantling of his community. He adds that the parliamentary seat planned for the Shabaks has become an object of transactions between the big political forces. As a ripple effect, this fait accompli deprived the Shabaks of their rights and real democratic representation. Indeed, the representatives of the minorities in parliament do everything to satisfy the demands of the political forces that support them, to the detriment of the interests of their community.

According to Mr. Bachir, three elements cause disputes within the Shabak community in Iraq: political money, land and power. Today, one actor in particular has his hands on these three subjects in the plain of Nineveh: the Iraqi militias.

“A Shabak regiment is also part of the force of the Hashd al Shaabi or Popular Mobilization Units, a force generally considered affiliated with the interests of Iran,” explains Mr. Bachir. The Shabaki Nineveh Plain militia, known as the Nineveh Plain Forces, is known for the numerous abuses it committed against other groups in the region, although it is not the only one to have committed such crimes.

For his part, the Yazidi journalist Dhiab Ghanem underlines the existence, since 2003, of

struggles between the Democratic Party of Kurdistan and the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan in the region of Sinjar, one of the electoral strongholds of the Yazidis.

After the Daesh attack in the Yazidi regions in 2014 and the fall of the Iraqi and Kurdish military systems, the Yazidi electoral vote was considerably fragmented due to political pressure from local actors. This has caused a dispersion within the community itself. The Yazidi community was further fragmented at the end of 2020 by the blatant interference of the Kurdistan Democratic Party in the election of the new Yazidi spiritual leader.

Deceiving results

Mr. Ghanem was eager to reminds us that there are more than one Yazidi Member of Parliament today. The minority quota seat was obtained by a representative of the Yézidi Taqqadum Party (ETP) close to the central government in Baghdad, while three representatives of the PDK and a representative of the Patriotic Union of Kurdistan (UPK) are also Yazidis but affiliated with the interests of their parties.

Regarding the Christian minority, the Al-Babiliyoun movement won 4 of the 5 seats dedicated to his community. The fifth seat was won by the independent candidate from Erbil province, Mr. Farouk Hanna, supported by the Iraqi Communist Party of Kurdistan.

At the same time, the Sabaean quota seat was won by the independent candidate for the Baghdad constituency, Mr. Osama Kareem Khalaf who later joined the independent group in Parliament close to the Tishreen movement.

Mr. Houssein Ali Merdan won the only seat of the Kurdish Faylis quota. The seat destined to Chabaks was won by the independent candidate Waad El Kadou, close to the Fatah movement. For the first time in years, two women from the Kaka’i community have entered the Iraqi Parliament: Najwa Hameed from the Kurdistan Democratic Party and Ahlem Ramadan from Nineveh, a member of the Kurdistan coalition. This is the first time since 2005 that the Kaka’is are present in Parliament.

Despite a popular uprising that saw the overthrow of a corrupt and inefficient government, despite numerous promises of reform and the adoption of a new electoral code intended to strengthen the representation of the country’s many minorities, it appears that all efforts towards a better political representation in line with Iraq’s societal reality were opposed by old-fashioned political calculations, where the larger players eat the small ones. By co-opting candidates from minorities, the traditional parties dictate their own agenda instead of letting the communities handle their own fate. The risk of seeing cultural minorities of Mesopotamia (historically so numerous and constitutive of the Iraqi identity) sink into oblivion under the weight of political calculations, or of becoming entangled in a subordination contrary to the very idea of their parliamentary existence.