Years after the defeat of the Islamic State, the large iraqi-syrian border is still very fragile and easy to break through. Whether they exploit the vast emptiness of the desert or the corrupt militias and border guards, IS terrorists have found many ways of maintaining their mobility on the borders and still represent a major threat in Iraq. Despite the disappearance of the so-called islamic caliphate, ISIS terrorists have managed to keep operating sleeper cells that regularly target civilians, government employees or military personnel. The 600 kilometres-long border between the two countries remains a weak spot due to its geographic, historic, and social specificities that makes it almost impossible to control.

Earlier in February, the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) announced the arrest of two people on charges of smuggling ISIS terrorists between Iraq and Syria. This news came just days after the SDF launched a new military operation against ISIS in cooperation with the international coalition forces.

Corruption on the borders

Although Iraqi authorities spent hundreds of millions of US dollars in order to install sophisticated surveillance equipment, they have not yet hired the suitable personnel to operate this technology, nor have they developed an efficient way to counter corruption on its borders.

Smugglers have close ties with corrupt border guards, according to a high ranking officer, who requested anonymity and told the Red Line: “[t]he smuggling of ISIS terrorists from Syria to Iraq continues, due to the corruption of some border guards.”

He pointed out that “the smuggling process takes place in exchange for sums of money per person reaching up to 2500 US dollars.” The money is paid in exchange for bypassing the security checks for those wanted by the authorities, he continued.

In order to eliminate the smuggling, or at least reduce it, our source added: “a highly professional force of border guards, under constant supervision, has to control the borders.” Such a requirement is not being implemented in the present.

Iraq’s soft underbelly

The syrian border is a huge challenge to Iraqi federal authorities due to numerous complexities existing on both sides of the fence. In the two countries, The recently liberated region is coping with inner conflicts between the victors following the defeat of the ISIS terrorist organization that used to control the border area.

The region of Sinjar is one of the most affected by the power struggle between the rivals most notably the PKK, the Kurdish Regional Government, and the Popular Mobilisation Forces. Earlier in 2019, the head of Ezidxan protection force affiliated with Kurdish Regional Government, Hayder Shashu, accused the PKK members of smuggling ISIS terrorists into Sinjar region (northern Iraq), calling on the Iraqi authorities to take suitable measures to address “the PKK’s threatening activities.” In exchange of between 4 to 10 thousand USD, depending on the rank of the terrorist, ISIS members are claimed to have found a way through to enter Iraq. Although Shashu is hardly an objective actor of the region, himself being close to the Kurdistan Democratic Party that has sought to dominate Sinjar for years, his comment shed some light on the rivalry existing between different actors on the ground. “Yes, PKK may have smuggled some individuals related to ISIS from time to time for some money. But absolutely everyone does it in the area. It’s an extraordinary way of making profits”, commented a researcher specializing in the Sinjar area that spoke under the condition of anonymity.

The Syrian-Iraqi border, which represents a weak spot to the security of Iraq, is also a breather for the Syrian regime. The network of Iraqi militias (all close with Syria’s baathist regime) operating on both sides of the borders has created a bridge connecting the Syrian regime with Iran, according to the security analyst, Saad Jabbar.

As vital as the region is for the continuity of the Iranian influence in Syria, these militias are obstructing any serious attempt to control borders Mr. Jabbar told the Red Line, adding: “[e]ven if we do not want to accuse the militias’ networks of smuggling terrorists, it’s obvious that their indirect involvement keeps the region unstable as they undermine the strength of federal forces and institutions. This situation makes the smuggling of criminals all too easy.”

Iraq’s Prime minister Mustafa al-Kadhimi, has been repeatedly asked to send Counter Terrorism Services to border regions, except these demands were not answered due to political pressures. Instead, several Iraqi army units are conducting regular operations to thwart ISIS threats. The most recent of these operations took place on April 4, where Iraqi military intelligence confiscated motor bikes, and boats that were prepared to smuggle ISIS terrorists through the Euphrates in al-Qaem district (Anbar governorate).

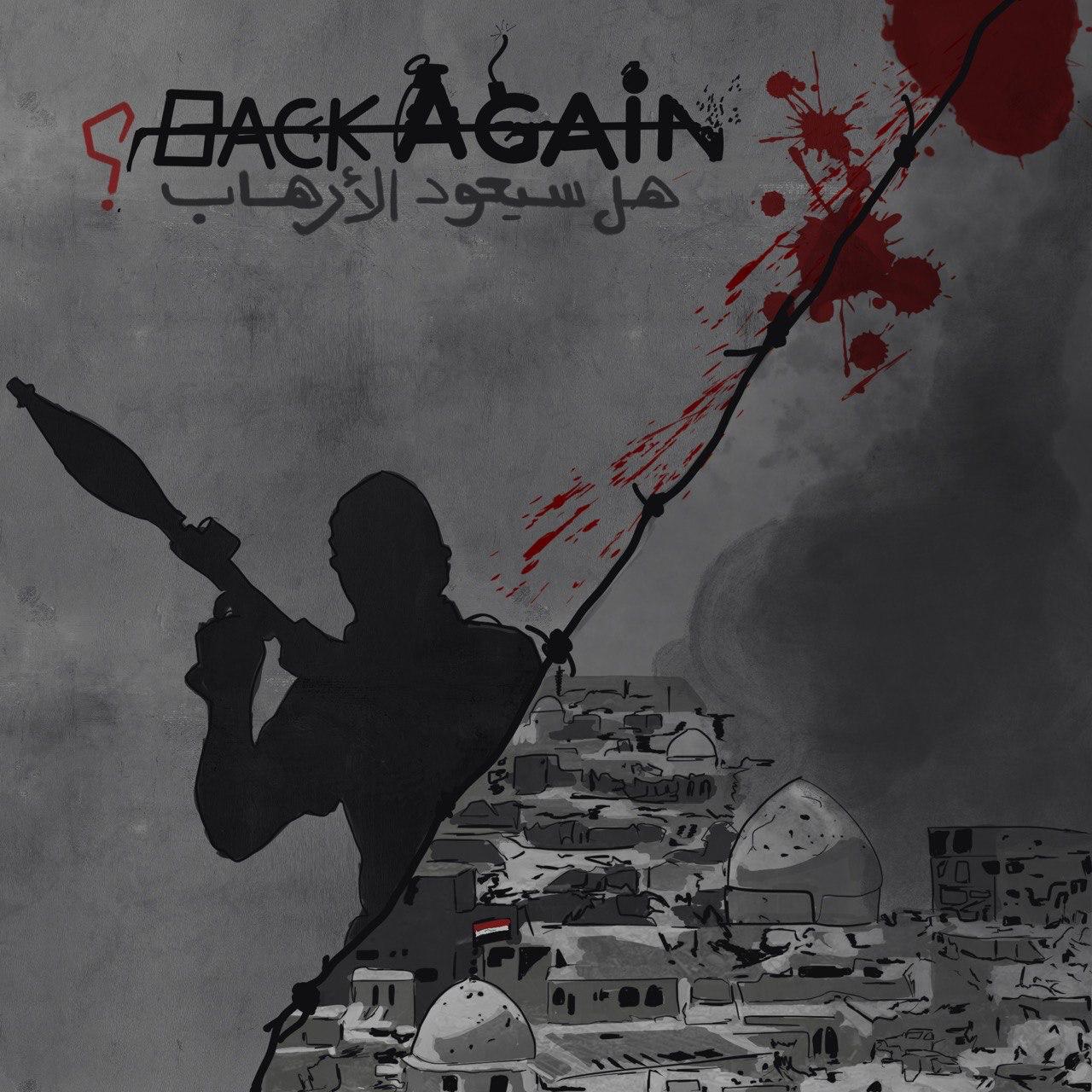

Fears of a terrorism resurgence

Earlier In August 2020, Major General Yahya Rasool, the military spokesperson for the Iraqi Prime minister, announced the arrest of 31 Syrians who tried to infiltrate into Iraq from Raqqa, stressing that “they were carrying hundreds of explosive devices.”

In the middle of political conflicts over Mosul’s resources and budget allocations, fears of the return of ISIS terrorists and the trauma of war are slowly regenerating in the city.

Anwar Aziz, a resident of Mosul, believes that the political struggles over wealth, positions, partisan rivalries, and the proliferation of armed militias in Iraq have led to neglecting the danger of the return of the ISIS terrorists. He also told the Red Line that “The return of ISIS families into society contributes to the spread of extremism and brings back the fears of another islamist insurrection”.

Mosul is Iraq’s second largest city, and the capital of the northern province of Nineveh. The city has been going through an endless turmoil since 2003 due to sectarian conflicts, corruption, and deliberate negligence of the federal government. All of that resulted in ISIS taking control of the city in 2014 before the government was able to reorganize its military forces and reclaim the capital of nineveh in 2017. The battle to reclaim Mosul from ISIS is the largest urban battle since Stalingrad during the second World War.

The Red Line correspondent made many attempts to obtain statements from government officials and border guards to know the extent of the disaster of ISIS smuggling, but to no avail.

However, an officer in the Iraqi Special Forces, who requested anonymity, told the Red Line: “There is great complicity by some members of the Border Protection Forces, as they cooperate with smugglers and bedouin shepherds, tipping smugglers about the unmonitored spots of the borders in the Jazireh area where they can operate in exchange of hundreds of thousand of dollars.”

Iraqi Ministry of Defense previously announced, on June 12, 2020 that the military intelligence had arrested the organizer of an ISIS smuggling network that used to transfer militants and their families between Syria, Iraq, and other Arab and European countries.

In recent months, attacks by ISIS militants have increased, especially in the area between Kirkuk, Salah al-Din and Diyala, also referred to as the Triangle of Death in Iraq. All in all, it appears that the smuggling of ISIS members is happening in front of officials benefiting financially from these operations or pursuing foreign agendas aimed at destabilizing Iraq’s security.

If Iraq wants a definitive salvation from the security disaster that burdened the country for several decades, security forces must intensify their efforts to eliminate criminal activities on its borders, either stemming from terrorists or other actors.

Although years have passed since Iraq reclaimed all of the national territory from ISIS, the authorities have not yet announced accurate numbers of civilian and military casualties of the war.

According to an Associated Press report published in 2017 revealed the The price Mosul’s residents paid in blood to see their city freed was 9,000 to 11,000 dead, a civilian casualty rate nearly 10 times higher than what has been previously reported, in addition to 3.2 million internally displaced people, before the battle for Mosul began in October 2016.

This number of casualties may not coincide with the death count produced by the British website Iraq Body Count, which specializes in calculating the number of civilian deaths in Iraq. Iraq Body Count announced that the number of civilian casualties in 2016 amounted to 16,393 people, while the previous year recorded the killing of 17,578 civilians.

Overall, this discrepancy of numbers reveals how dysfunctional the Iraqi institutions remain and lack in organization. Without stronger government bodies, Iraq’s borders will remain porous and prosperity will be an unreachable prospect.

- The Syrian Democratic Forces: is an alliance in the Syrian Civil War composed primarily of Kurdish, Arab, and Assyrian/Syriac militias, as well as some smaller Armenian, Turkmen and Chechen forces. Founded in October 2015, the SDF states its mission as fighting to create a secular, democratic and federalised Syria. The alliance played a key-role in defeating the Islamic State in cooperation with the international coalition.

- The counter Terrorism Service is a tactical force that was established after 2003 to counter insurgencies in Iraq after the US Civilian authorities caused the biggest security vacuum in the country’s modern history by disbanding security forces by removing all military commanders affiliated to the Baathis party. This division is one of Iraq’s best trained and equipped in use, in addition to its structures that have higher independence from partisanship than the rest of Iraqi armed forces.