COVID-19: a governmental failure

The Coronavirus started spreading in Iraq by the end of February 2020. The epidemic was made worse by government inaction on various levels, including deficiencies in raising awareness to the public about the (well known) dangers of the virus, or failure to close the borders to prevent the spread of the epidemic. Finally , the government decided to impose a curfew on March 17, 2020.

Earlier, on March 4 the spokesperson for the Ministry of Health, Saif Al-Badr, had confirmed that the sanitary situation in Iraq is made worse because of the lack of financial allocations but denied that the government was overwhelmed by the situatoin: “This lack of spendings is weakening our efforts to confront the epidemic.” also claiming that, “[despite] this government incapacity, [we] must admit that The Ministry of Health faced the epidemic adequately.”

During the spread of covid 19, many incidents of doctors and hospital staff being assaulted by patients’ families were reported. The repeated incidents led the medical staff to demonstrate on September 7th, 2020, demanding the activation of the Doctors Protection Law (the sixth legal provision of Doctors’ Protection Laws). The law states that “whoever assaults a doctor during the practice of his/her profession or because of its performance shall be punished”. They also requested the hiring of medical graduates from 2019 who still hadn’t been appointed to their position by the government, which is normally entitled to deliver positions to medical students after their graduation. However, these demands were not met.

The shortage of respiratory, and other medical equipment such as protective suits, masks and gloves was the overwhelming reality for most Iraqi hospitals in all governorates. Nonetheless, southern governorates have their own particularity due to high levels of poverty. It is also there that some social initiatives were born thanks to local philanthropists.

Samawah is the capital of Iraq’s southwestern Muthanna province, the poorest of all Iraqi provinces. There, the price of a mask reached 1.5$ a piece. To face these very high costs, Jawad al-Samawi, an Iraqi seamstress, began sewing and distributing masks for free. Al-Samawi decided to buy 100$ worth of medical fabric and make about 6000 masks every week. He would then distribute them to the people in his city relying on a group of young volunteers. In his interview to The Red Line, the tailor Jawad Al-Samawi, reminisced about his humanitarian role, helping to reduce the spread of the Coronavirus epidemic in Iraq:

“I put my professional abilities at the service of my city from the beginning of the epidemic, because I felt it was my duty.” he said.

According to hospital patients in Muthanna province, the teaching hospitals and medical centers in the province suffered from a near collapse of their infrastructures. Following this disaster, Muthanna’s health department did not give any explanations. Rather, the director of the province’s Health department, Basil Sabr, stated that “[all] Iraqi hospitals experienced a near collapse due to the absence of adequate financial allocations”, while also praising the initiatives taken for solidarity and cooperation between people.

Nothing but Solidarity

In other parts of the country, such as Mosul, which was significantly destroyed by the war against ISIS and never really recovered from it, the COVID19 epidemic brought additional pressure on the infrastructures. Here, solidarity initiatives were not limited to providing medical equipment to hospitals. They also included awareness campaigns initiated by local journalists.

Like other media professionals from Mosul, Saqer Hashem used his experience in media to organise awareness campaigns on social media, as well as distributing brochures and posters containing key details about the epidemic and stressing the importance of social distancing. “This work came as a spontaneous initiative that we decided to launch with my colleagues. It stems from our love for our city” Shaqer described to The Red Line.

At the same time in Mosul, more classic initiatives were also witnessed. Abdulaziz AlSaleh, 29 years old, is one of 6 activists who provided medical equipment and assistance to the people of the city. “There are three hospitals in Mosul, and they suffer a shortage of pretty much everything: oxygen, beds, medications, and protective equipment…” described AlSaleh when explaining what motivated their initiative.

According to Iraq’s Ministry of Planning, Mosul’s poverty rate exceeds 37.7% of its population. Additionally, there is only one medical bed for every three thousand patients. The spread of the epidemia increased the level of poverty in the city, while increasing cases of negligence by an overwhelmed medical staff.

After their working hours, many hospital employees recall undertaking voluntary initiatives to alleviate the suffering of the people in Mosul: “On top of our medical activities, there was huge humanitarian effort outside of our working hours.” explained Sorour Al-Husseini. Indeed, many medical staff in Mosul volunteered to help patients, while others donated oxygen and oximeter devices. They also delivered medicines to patients that preferred staying at home.

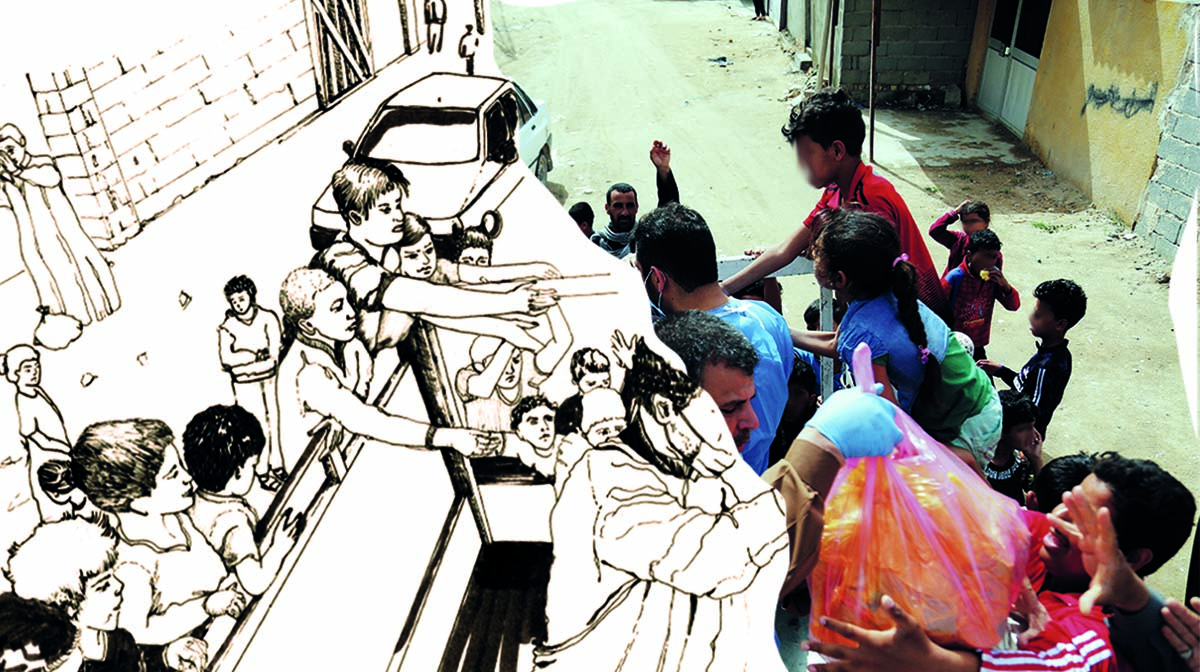

In the height of the COVID epidemic, it was as if solidarity had taken over the classic health facilities. People of Mosul were no longer waiting for someone to cater for their wounds, and tried to heal them themselves. in addition to health support, volunteers also provided food to the underprivileged ones: “Cooperation was not on the medical level only; activist teams also regularly distributed food baskets to help the poor that got even more vulnerable due to covid19.” the activist Ammar Iyad explained to the Red Line.

Water scarcity

On top of poverty, domestic violence, hunger and the rarefaction of medical supplies, citizens suffered from decline of drinking water quality and distribution after the imposition of a curfew by the government. In Wasit Governorate for instance, travel bans between governorates obstructed the delivery of food products and drinking water, which caused their prices to double. The impact was particularly severe in poor areas of the province. The crisis encouraged some volunteers to unite and take matters in their own hands. A team of thirty people thus gathered and started transporting drinking water to the slums of Wasit Governorate. The team delivered more than 4000 liters of water on a daily basis.

“We managed to significantly alleviate the water needs in the poor areas and slums. Our team also cooperated with the governorate administration to sanitize the streets and homes.” explained Ayar Tomaz al-Shammari, a 40 years old activist. He and his team continued their voluntary work by distributing oxygen bottles to recovering patients in their homes as shortages in public hospitals made it impossible for them to obtain treatment in hospitals.

Countering fake news

An important aspect of the pandemic that volunteers took very seriously is the spread of fake news revolving around the Covid19 epidemic. Many initiatives took place around the world to counter fake news and misleading statistics. These included erroneous information about the origins of the virus, about the methods of transmission, all the way to the so-called untold motives behind the upcoming vaccination campaigns. From the start of the coronavirus epidemic in Iraq, Dr. Raghad Al-Suhail, writer and virus researcher, started providing medical advice to people by launching an awareness campaign about the epidemic: “I started trying to educate the Iraqi public through my Facebook page, taking advantage of the number of followers and friends I have, and because I am a researcher in the field of virology. My credentials helped me a lot in this awareness campaign.”

Al-Suhail started her campaign by referring to the importance of wearing protective medical masks, and gloves. She also spoke on the importance of sanitising shopping bags, food and vegetables, as well as the need for social distancing: “I was driven by my concern for my Iraqi fellows as well as my sense of responsibility towards them.”, she told The Red Line.

As fake information kept spreading in the country, Raghad Al-Suhail was one of the first to address the dangers of false rumors and the harm they may cause to society. Al-Suhail and other activists also shed light on the dangers of targeting the medical staff and blaming them for the poor results of Iraq’s health system.

Collapsed health sector

The Covid crisis showed the extent of the vulnerability of Iraq’s health sector. Amid the peak of the epidemic, a number of doctors in Baghdad’s Al-Karkh Health Department Hospital posted pictures of expired protective medical equipment. A nurse called Atika, from Yarmouk Hospital in Baghdad publicly confirmed the story and was punished by her hierarchy by being transferred to The outskirts of Baghdad.

Joined by The Red Line, the director of Al-Karkh Health Department in Baghdad, Mr. Jasb Al-Hijami did not deny what happened to Atika, adding that the measures taken against her were taken to avoid social unrest: “We try to avoid causing confusion, and certainly, people should not get affected by what is posted on the web; it’s misleading and exaggerated. Also, stories often get distorted by those who share them on the internet.”, he stated.

Iraq’s poor health management capacities encouraged social solidarity during the COVID19 crisis. This proves that Iraqis have developed a parallel social system since 2003, which keeps growing in importance, especially in times of crisis. Since the fall of the Baathist regime, successive governments have literally been living in parallel universes in which political conflicts and constant struggle for resources and power forced Iraqis to depend on themselves rather than depending on the state that neglected its obligation.